A recent trip through the Pilbara showed widespread establishment of buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris). It was looking impressive on many properties following substantial rain across the region in May. While the presence of a palatable perennial grass is good news for graziers it is a major problem for anyone managing native vegetation areas in National Parks and Nature reserves.

Buffel grass changes the ecology of the area. While we tend to think in easily visible species such as kangaroos and wallabies which no doubt also find buffel grass good tucker. On the other hand there are small marsupials, rodents, reptiles and other animals we rarely see that find their environment vastly changed, often to the negative.

Probably the best stand was in the Cape Ranges National Park near Exmouth where it was 70 to 90 per cent ground cover.

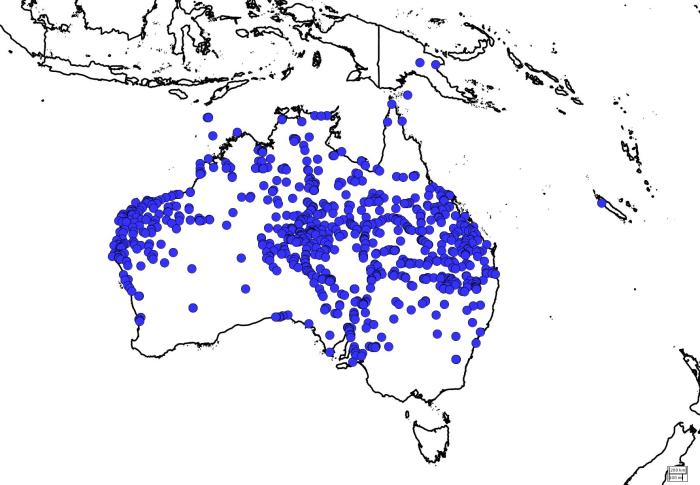

Distribution of buffel grass in Australia. Source:Australian Virtual Herbarium

Distribution of buffel grass in Australia. Source:Australian Virtual Herbarium

Another issue that was obvious on our travels was that many properties had very little ground cover or feed, despite heavy rain 4 weeks before. It would be reasonable to assume that most of the water ran off without entering the soil due to the lack of ground cover. The image below shows how little soil cover there was despite reasonable recent rains.

Grazing exclusion zone (background) showing potential groundcover versus actual groundcover (foreground).

Grazing exclusion zone (background) showing potential groundcover versus actual groundcover (foreground).

For more information on buffel grass go to:

http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/347153/awmg_buffel-grass.pdf